America in the First World War is known for her deeply anti-German sentiment. In a previous post, “To Hell With the Kaiser: Anti-German Sentiment in Gettysburg,” I mentioned some inklings of evidence for anti-German sentiment in the town and surrounding area. My research since that time has yielded even more evidence for anti-German activities in Adams County.

In his book, Over Here: The First World War and American Society, historian David Kennedy presented early twentieth century America as akin to George Orwell’s Oceania in the book 1984, a society with unparalleled censorship and blind hatred towards perceived enemies. At the outset of this study, it seemed doubtful that the kind of rabid censorship and paranoia of Washington, D.C. officials could have made a huge impact on a community as small as Gettysburg. I was wrong. In 1917, German spies and conspiracies were seen in anything and everything. When the Remington Arms Company located in Philadelphia blew up, Gettysburg was quick to blame German-American sabotage. No mail coming from or going to Germany would be accepted by posts offices, Gettysburg’s included. On April 21, 1917, two Adams County boys, Charles Keagy and Albert Kline, were arrested as German spies because they were overheard speaking Pennsylvania Dutch at a train station. In the heart of Pennsylvania Dutch country, suddenly heritage became suspicious and dangerous. After being questioned and released, the “American Kaiser-Wilhelms” were followed by Secret Service agents to verify the boys had told the truth about where they were headed.

Gettysburg, a town rife with German names and Pennsylvania Dutch heritage, seems to have made an effort to overcompensate to prove their Americanism. The irony is profound. At any given week, somewhere in Adams County there were three or four patriotic rallies filled with citizens with German last names damning the Kaiser and his Kultur.

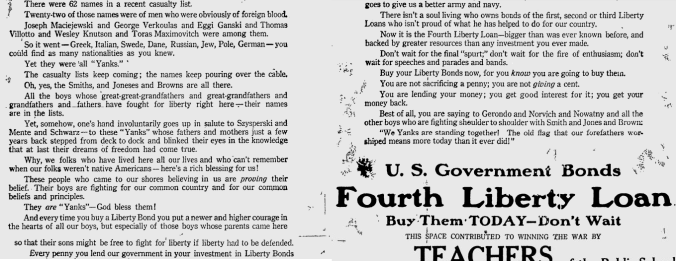

Gettysburg Times, August 17, 1918

In January of 1918, President Wilson passed a proclamation that all male German aliens (still holding German citizenship) over fourteen years of age must be registered. Each man had to present himself to the local post office on the specified day, be photographed, fingerprinted, and provide personal information and business contacts. The registrant than had to carry a card showing he had been certified and authorities could ask to see the card. If the registrant wanted to move from one house to another, he first had to obtain permission from the local chief of police before he could move. One would not expect to find this kind of surveillance in rural Adams County, but on the appointed day, four aliens residing in the county were registered. The names and places of employment of each of the four men was printed in the Gettysburg Times. Only one, Rudolph Adolph Schultz, resided in Gettysburg and was employed as a chef at the Hotel Gettysburg.

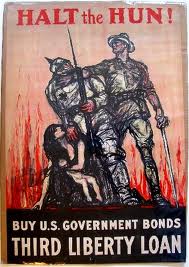

Continuing their patriotic efforts, on May 6, 1918, a Liberty Parade was held in Gettysburg. In addition to the marching soldiers, maypoles, and children in patriotic outfits that is to be expected at such events, the parade featured sinister undertones:

“The high school pupils had a burial party which was conveying a coffin on a bier labeled, “Bill, the Hun; the old dog is dead,” while immediately behind came three grim looking grave diggers each armed with a business-like spade. Another Kaiser was carried about suspended from a rope while the third was dragged along without much ceremony.”

Although this is not Gettysburg, displays such as this would have been seen in town throughout the war. LC-DIG-ggbain-26914

Grave displays such as this makes one wonder what was going through the mind of Rudolph Schultz, the only card-carrying registered alien in Gettysburg, as the Kaiser was hung in effigy and paraded through the streets. Barely a month earlier, Robert Prager, a German coal miner living in St. Louis, was lynched in front of a crowd of 200 people. Did Schultz feel threatened? Did he avoid the parade altogether? Was he actually a target for anti-German sentiment? These questions cannot be answered, but one gets the impression that pro-German sentiments would not be dealt with kindly in Gettysburg from 1917-1918.