100 years ago today, The Gettysburg Times ran a second page article about a massacre of Armenians at the missionary compound in Urumiah, Persia (modern-day Urmia, Iran). The article reported that Turkish forces beat and insulted American missionaries before going on to kill Armenian Christians who had taken refuge at the mission. Gettysburg heard about the massacres through the American consul in Tabriz, Gordon Paddock. Paddock would continue to transmit messages throughout the genocide, keeping Americans aware that these acts were happening.

The Armenian Genocide (some use the term massacres since “genocide” was not coined until the Second World War) of 1915 remains a deeply controversial and contested event in the legacy of the war. There is overwhelming evidence to prove that it happened; in 1915, Turkish forces systematically began forced removals of Armenians and organized an effective killing operation that annihilated 1 million out of 1.8 million Armenians in less than a year.* However, in an act of purposeful historical forgetfulness, the newly created Turkish government that succeeded the Ottoman Empire in 1918 refuses to acknowledge that it happened. The current Turkish narrative is the Armenian population present within the Ottoman Empire was deemed a security threat and thus forced to move. In the course of relocation, some Armenians died. This narrative utterly disregards historical reality. 1 million out of 1.8 million dead is not an unfortunate accident.

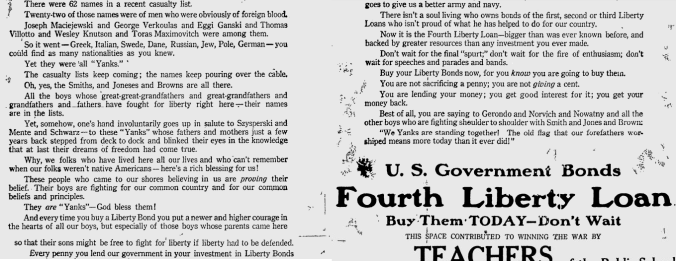

In recent news, Armenians have been actively seeking recognition for the genocide of their ancestors. Although the Vatican remains officially neutral on the issue, Pope Francis called the event the “gravest crime of Ottoman Turkey.” On March 7 of this year, an Armenian delegation went to the Vatican to seek a more official recognition of the genocide. Since 2009, the Armenian Diaspora has been seeking the official recognition of the Obama administration. As of yet, there has not been an international recognition of the genocide for fear of upsetting current relations with Turkey. March marks the beginning of the centenary of the Armenian genocide, anticipate the event to be in current events. The contemporary issues surrounding the Armenian genocide of 1915 demonstrate the First World War’s continued legacy on the 21st century world.

![This disturbing photograph, taken in 1919, demonstrates continued killing beyond the 1915 massacres was originally captioned: "The Turks' bag of game: This picture shows that the Turks, in the remote districts of Aisa Monor [i.e. Asia Minor] beyond the reach of the protecting hand of the Allies, have continued their policy of the slaughter of the Armenian Christians after the signing of the armistice. The massacre of the forty shown in the picture, which has just been received in this country, occurred in February 1919." LC-DIG-ds-01042](https://johnsa07.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/lc-dig-ds-01042-graphic.jpg?w=676)

This disturbing photograph, taken in 1919, demonstrates continued killing beyond the 1915 massacres. Originally captioned: “The Turks’ bag of game: This picture shows that the Turks, in the remote districts of Aisa Monor [i.e. Asia Minor] beyond the reach of the protecting hand of the Allies, have continued their policy of the slaughter of the Armenian Christians after the signing of the armistice. The massacre of the forty shown in the picture, which has just been received in this country, occurred in February 1919.”

LC-DIG-ds-01042

Alan Kramer, Dynamic of Destruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007)

Chapter Two in Stephane Audoin-Rouzeau and Annette Becker, 14-18: Understanding the Great War (New York: Hill and Wang, 2002)

Michael Neiberg, Fighting the Great War: A Global History (Harvard University Press, 2006)